Smiley And Me

January 26th, 2024

A benefit of rewatching something is that, freed of the need to assemble the events into a coherent narrative in my head, I can focus on other details. During a recent rewatch of Do The Right Thing, Smiley caught my attention. He’s a marginal character not present in the original screenplay, and while rarely the center of any scene, his presence makes several moments significantly stronger. Particularly the exclamation point on the film’s climax: Martin and Malcolm pinned to the wall of fame. But most of all, what caught my attention is that I know Smiley.

⁂

I have art hung on nearly every wall in my home. Still more sitting on shelves, or in folders, awaiting some way to reasonably display it. Much of it’s from local artists, out of a desire to support living artists, and also a desire for geographically situated work. By no means is this a large collection, but I feel relatively confident in claiming that I’m the foremost collector of one particular artist.

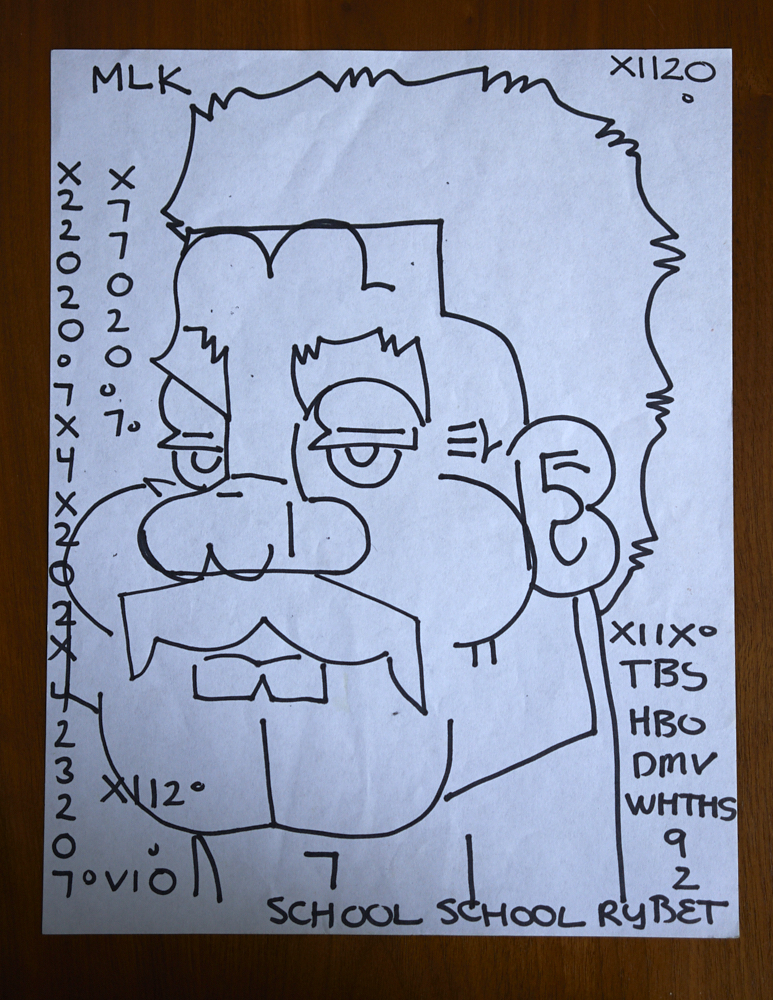

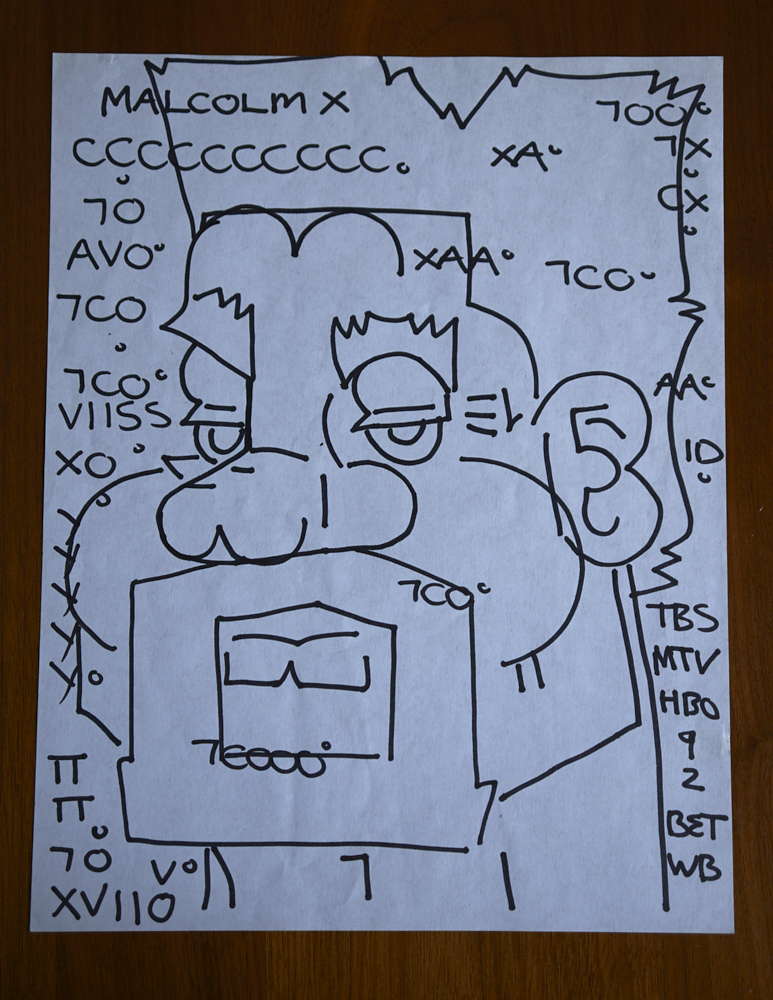

There’s no way for me to confirm that I have the largest collection of this artist’s work, for the same reason that these last sentences have been tortured with indirection: I don’t know his name. Or to be more accurate, he and I have only ever communicated verbally, and so I don’t know how to write his name. I know he sometimes signs his work “SRCY”. And I know he says his name like the Greek goddess “Circe” (or “Cersei” in Game of Thrones).

Up until 2020, I’d regularly run into SRCY on the street, selling his sharpie-on-paper drawings. He was a regular in my neighborhood, and though he didn’t live there anymore he still called it home when we spoke.

SRCY, like Smiley, wasn’t the easiest person to communicate with. On good days he’d recognize me as “Stephen”. On the average day it’d be a hug and “hey Daddy”, a familiar term of address I wasn’t always comfortable with but was still happy to hear. On the tougher days, there wasn’t any glimmer of recognition. Just the price per drawing.

SRCY and I lived in different cities that happened to occupy the same space. Like a layer of oil sitting on top of water. Any agitation of those layers through our interactions was a temporary disturbance. In time those layers would re-settle. Cohere. Repel.

⁂

Smiley appears, unscripted, in my favorite scene in Do The Right Thing. Sal and Pino are chatting in the pizzeria about Pino’s hatred of the residents in the neighborhood, and Pino’s desire to relocate the pizzeria to their own, Italian, community in Bensonhurst. Sal squashes the idea, and makes an economic argument for remaining in Bed Stuy. Smiley then interrupts the conversation by banging on the window, offering his pictures. Pino threatens him and chases him off the sidewalk, upsetting the guys on the corner. In an attempt to make peace, Sal comes out to offer a few dollars to Smiley for his picture.

Pino and Sal appear to have the same position with respect to Bed Stuy. This isn’t their community. Sal’s concern in financial. It’s more lucrative to maintain a presence in Bed Stuy, but there’s no sense of communion with the people on the block. Sure, he offers Smiley a few dollars, but that only highlights his posture towards the neighborhood. Sal has transaction histories, not relationships. He gets to watch these kids grow up, but strictly as customers1.

There was considerable debate, both on the set between Sam Aiello and Spike Lee, as well as since release, about whether or not Sal is a racist. I don’t think that question’s particularly interesting. More interesting is asking “why is racism useful to Sal?”. The fixation on Sal’s status as a racist provides potential white viewers with an escape hatch. They’re saved from assessing the broader power dynamic, from considering racism as a tool that can amplify other existing power dynamics. That viewer may conclude that, since they themselves aren’t racist, they’re different. They’re safe. But a non-racist Sal could still get the police to kill Radio Raheem. As Sal reminds us himself, there’s no freedom in the shop, and his “I’m the boss” stance doesn’t stop being true outside the pizzeria’s doors. The dominant culture ensures that.

⁂

I was chatting with two coworkers at a train platform on our way to a baseball game. As we were speaking, a Black man approached us and began to say something. Only a few syllables into his question, one coworker interrupted him. Without even looking over, he waved his hand as if to say “stop” and said “sorry, I don’t have any cash”. I turned to the man and called his name: “SRCY!”, and he gave me a hug. SRCY and I chatted for a bit, I perused the work he was holding, and I ultimately bought a couple pieces.

I thought about that interaction all game long. I thought about the ease with which that coworker, a white self-avowed liberal, concluded with instinctual reflexes that this person wasn’t part of his community, and was in need of dismissal. The maneuver wasn’t mysterious. I also thought about how my few dollars for his art didn’t refute our estrangement. How much of that gesture was true care, and how much was, like Sal, paying the tax against my guilt?

Do The Right Thing, in fictionalizing a single 24 hour period, can only depict so much. And Lee’s populating of the cast with archetypes imposes limits on any reading about these individuals. Nobody really knows a Buggin’ Out, because we don’t even know Buggin’ Out. Regardless, these types rhyme with reality, then as in now. Obviously SRCY isn’t Smiley, but Smiley is a lens through which to revisit my relationship to him, and the movie is a lens through which to revisit my relationship to this place.

⁂

For the longest time, one of my greatest wishes was to live some place with a stoop. All I wanted to do was be able to sit on the stoop of my home, in the sun, and be. And this one block in Bed-Stuy is filthy with stoops and stoop-adjacent public spaces. Stoop heaven. And they’re all alive with people.

I last saw SRCY in early 2020. The onset of COVID muted a relatively busy neighborhood. The spectre of infection and death loomed over any outside interactions, and people disappeared into their homes. Then, I moved five blocks away to a place with a stoop. Five blocks may not seem like a lot, but all the familiar faces of the decade in and around my previous apartment were gone. As I was moving out, two different building-mates invited me into their homes for the very first time. After ten years of interactions (and one big fire alarm scare), the preciousness of community revealed by the pandemic, combined with my moving boxes, demanded some action to stem the loss.

That neighborhood came back, but different. I sit on my stoop and read in the sun, but I don’t really see anyone walk by. I think about all the faces that didn’t return, and SRCY’s in particular. I still look for him when I’m walking around the city, or on the bus. I missed my chance, if there even was one, to forge real community with him.

I don’t know who to talk to about SRCY, and I don’t know how to write about my memories either. Is it presumptuous to miss a person whose name you can’t even write? Yeah, probably. In another film, Drylongso, the protagonist Pica takes polaroids of Black men in Oakland in order to produce some proof of their existence. I don’t have any pictures of SRCY, but I have his work, and I have a diptych that feels right.

1 We’ll leave the case of Jade alone for now